The core of information and photos come from two sources - Our Continent published in 1882, by Donald G. Mitchell - Artistic Houses: Being a Series of Interior Views of a Number of the Most Beautiful and Celebrated Homes in the United States, published in 1883-84, by George William Sheldon.

Tiffany kept his studio at the Association Building for nearly a decade, until 1878. By that time he had been married for six years and had two children. The growth of his family prompted Tiffany to look for quarters larger than those the family had been occupying in the home of Tiffany's father. He settled on the newly constructed Bella Apartments, a block from Madison Square, dubbed by O. Henry "the fly-eye of New York". It was three blocks away from the Association Building.

At the "pupil" of this most fashionable part of the city were a placid green park, with its flowering gardens, statuary, fountains, nannies, and baby carriages. Horse and carriages rattled around the Square - the pivot from which one "would see the world" - passing the striped awnings and wrought iron fence of Delmonico's, the grand Fifth Avenue Hotel, the old steepled Madison Square Presbyterian Church, aristocratic brownstone mansions, and Gilmore's Garden (soon to be renamed Madison Square Garden).

Throughout the 1870s New Yorkers saw apartment houses erected in ever increasing numbers, and many families whose backgrounds and social position would have led them to private houses in an earlier generation now lived in apartments. The Bella was observed as having the best class of fittings and style. The architect William Schickel designed the Bella of brick with stone trimmings in 1878. Every Bella household had at least one live-in servant, several had two and one family had three; all the servants at the Bella were Irish.

Developer of the apartment Oswald Ottendorfer christened the building "Bella," after his daughter. The Bella housed eighteen individual suites of rooms, two per floor in each of two five-story sections, one facing Twenty-sixth Street and the other facing Fourth Avenue***now Park Avenue South***, and two commercial spaces on the ground floor. Shortly after its opening the elegant building was described as one "exclusively devoted to domestic life and comfort. It incorporated a number of lavish features, such as polished granite columns and marble floors in the entranceway, with ceilings and walls covered in ornamental fresco, as well as many innovations, including a hydraulic elevator and a heating system of direct radiation from steam pipes. It was especially noteworthy for the abundant light in the rooms, a feature that must certainly have appealed to Tiffany. Indeed, Tiffany selected a suite on the top floor in order to profit from the additional light afforded by skylights. This large, grand apartment meant a slight increase in rent for Tiffany, as the suites ranged from $750 to $2,000 per year.

|

| Bella Apartments - 48 East twenty-sixth Street - New York City |

Additional information inserted signified by ***

***Beginning text of Sheldon's article***

Mr. Tiffany's flat, in East Twenty-sixth Street, has special interest as an exposition of his views on the subject of the interior decoration of houses. It was by the effort to overcome the difficulties presented by his apartments, in their crude and raw state, that this artist was led into the systematic study of the principles of the profession which he is now practicing.

| In the Fields at Irvington - Louis Comfort Tiffany - 1879 |

The chief apartment is the drawing-room, and here the visitor encounters one phase of that very delicate Moorish decoration which, in Mr. Tiffany's judgment, is best suited to such a place. By Moorish decoration the reader is to understand, not a copy of anything that ever has existed or still exists, but only a general feeling for a particular type. The effort has been in direct opposition to external fidelity to an original. All that was striven for was a simple suggestion of the ancient Moorish style, the artist believing that an entire rendering of it, or of any other, would have belittled him, besides being impossible; for something of its spirit would necessarily have escaped him in these later days, when his environment is so different from that of the Moorish decorator himself. Throughout Mr. Tiffany's rooms, indeed, the visitor will be struck by the absence of any token of servile imitation. A variety of styles present themselves, but not one of them is a copy. In this drawing-room, for instance, the Moorish feeling has received a dash of East Indian, and the wall-papers and ceiling-papers are Japanese, but there is a unity that binds everything into an ensemble and the spirit of that unity is delicacy.

Let us look at these paper-hangings. The tone of the ceiling is buff with blotches of mica, the latter shining much more brightly than silver, and being so admirably adapted to its purpose that attempts - unsuccessful as yet - have been made by American manufacturers to use it in the execution of their wall-paper designs. The secret still remains with the artistic Japanese, who, in addition to making a wall-paper paper much finer than the heaviest French specimens, have the faculty of so working in the flat that the material always looks like paper, and always expresses the quality of paper, and not of anything else. On the east side of the room, the ceiling comes down two or three feet to the frieze; on the west side, its paper melts into another variety, and produces its own special effect. The prevailing ground of the walls is pink, and it is curious and interesting to note how pleasantly this tint supports the hues of a watercolor picture by Mr. Tiffany - the "Cobblers of Bouffarik" - which hangs in a wide frame of very low-relief. The artist has tried to keep relation of the whole work, frame and picture, flat, as a part of the wall, and, by it so doing, to prevent the picture from disturbing the line or color scheme of that part of the room, and from missing the needed light which a projecting frame would have shut off. He desired that the picture, so hung, should look better, should have more to say for itself, than if placed elsewhere, or otherwise. He purposed that it should enter into the general scheme of its surroundings, and be at rest; in other words, that it should meet the fundamental artistic requirement of repose. It is self-contained and serene, and its environment ministers to its peace.

A screen with light Moorish columns separates the drawing-room from the hall, and between the columns are curtains of old Japanese stuffs, hung by light brass rings on light brass rods - so light that the weight causes them to sag. From a yellow against a blue below, the scheme of color of these curtains rises through a series of more and more delicate tones into a neutral, broad effect of lattice-work of linen cord, partly hidden by a fringe of the same material. The sagging of the brass rods is considered appropriate and natural, and the columns and the curtains go together admirably.

The four long windows on the north side, which the artist found when he began to decorate the room, and which, had he been consulted by the architect, would have been one double window, leaving the wall less cut up, and the lights and shadows less broken, have been dealt with in part. Two of them are treated together, by running across their tops a wide band of stained-glass work, and across their bottoms a comfortable divan, where the guest sits under shadow.

| Mirror on dividing wall - Drawing Room |

***The decoration of the drawing room combined a variety of styles. Tiffany's collections of Chinese and Japanese pottery and porcelains were displayed there, and a mosaic of Oriental carpets of varying sizes covered the floor. Antique Japanese textiles hung between slender Moorish columns, separating the drawing room from the hall.***

| Close-up of table in Drawing Room |

| The table sold for $182,500 in 2010. |

***The dominant piece of furniture was a cherry table in the center of the room. Its rectangular top was supported by slabs at each end, on shoe feet, with a long flat stretcher in between.***

|

| Imported textile printing blocks from India used for table support. |

|

| Imported textile printing blocks from India used for table support. |

| Spiderweb pattern fireplace screen made of mica. |

| Iridescent glass tiles flank fireplace opening. |

Step into the hall, and the contrast is intense. You have gone from delicacy into roughness. The wood-work, desired to be in a tone that would seem vigorous in a half-light, was painted a bright red; and the half-light effect obtained by perforating a circular burner so many times that the gas would come through it flickering, like the flame of a torch.

| A blunt gas jet attached to the wall by its hose. This jet was placed there to cast a flickering light on the stained-glass window behind it. |

an impression of mystery and indefiniteness; and the color in this semi-dark place is kept agreeable by being kept warm. The rough pinewood of the beams of the ceiling is gouged in many places, and ornamented with heavy nail-heads, to make it rougher still. The stained glass-work consists of very rough pieces; and the old Flemish tapestry that hangs at the entrance to the dining-room is rough, too, in execution and design. It is easy to see that in this small hall Mr. Tiffany has made himself felt; and one notable feature of it is that the expense has been next to nothing.

| This gabled section was painted brown, and the walls, parts of them covered by bronze and bronze studs, a warm India red. |

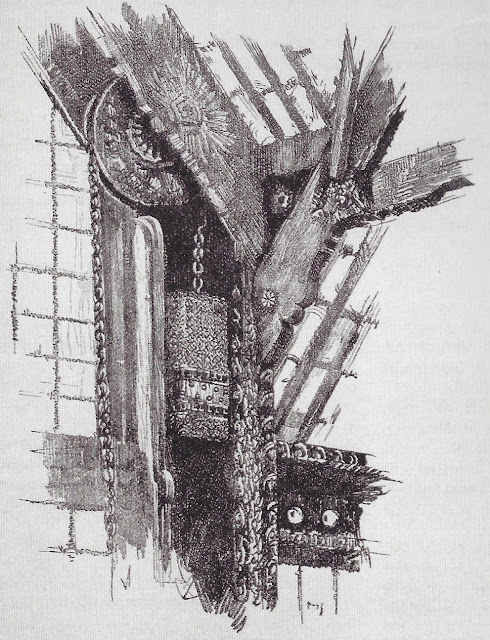

***A large exposed wood wheel and weight on a chain facilitated raising and lowering the glazed upper half of the door opening onto the stairway. Tiffany did not hesitate to show openly the mechanical devices necessary to his designs. The engineer in him liked to solve mechanical problems. It also offered tempting financial rewards. Rather than install sliding folding doors or casement doors between the library and the drawing room of the Bella apartment - such doors consume space - Tiffany devised a rolling glass screen. The screen functioned as a decorative panel against the wall of one side of the passageway, allowing movement between the rooms; when privacy was desired, it could be rolled on large spinning wheel-shaped wheels to block the passage, and an attached Japanese silk curtain was drawn over it. As Mitchell pointed out, the spindled wheels complemented the decorative Japanesque swirls and circles on the wall treatment along the frieze, and the translucent glass panels of the screen were marked by a subtle pattern of weblike vines, which, when the screen was open, overlaid and intensified an identical pattern on the wall behind.***

***Weapons of various kinds, from a Moorish gun and Caucasian dagger to a European or American flintlock rifle, hung on the walls of the lobby and were stacked near it in a haphazard way.***

| The abstract design of the window was inspired by one created by daubing the residue of Tiffany's palette knife. |

| Owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not on display. |

***The experimental nature of the lobby window may have been matched by that of another window, which divided the library and the dining room of the Bella apartment. The panel is not known to survive, but Donald Mitchell's contemporary description suggests the novelty of the glass that was used as well as the panel's duality, as a window and as a mosaic. Mitchell wrote: "The qualities of the new opalescent glass are such that it is hardly less beautiful to look upon against the darkness, when it has good light from within, than under transmitted light. It offers to the eye under these conditions a great, glowing, sparkling field of mosaic, set off with wavy lines of golden leadings." Like the lobby window, this panel was noteworthy for its textural qualities. It was made from heavy, chunky colored glass rather than from the traditional thin, even glass. Mitchell describes the window as having "thick, irregular, broken masses; not large, but each with a half dozen facets, flashing and refracting light-a series of jewels of red, or golden yellow, of blue, of topaz, inserted into perforations of the wood," giving it the appearance of gems.***

***The entry space gave the visitor "an impression of mystery and indefiniteness," created in part through the unusual lighting effects from a circular burner overhead that was perforated "in such a manner that the gas comes through it flickering like the light of a torch," or like that of early American perforated tin lanterns. At night it all glowed in the flickering (and flattering) light from a gas torch of his own design, a metal cone pierced with small holes and supported on a standard about shoulder high.***

| Adjustable hood, pierced randomly |

We leave it for the dining-room. Here the furniture of American oak, with its fine blotches of grain, and Japanese mushroom wall-paper, with ceiling to carry out a sort of tiling with blue plaques, impress by their simplicity and by a certain strangeness, as if the host had sedulously endeavored to express himself, irrespective of other men, and had done so, all the while, under the restraining influence of a liberal education.

| Old leather trunk used as a hanging cabinet. |

***The coloration of the walls lightened toward the ceiling. A band of stamped leather in a rich bronze extended above the dado and served as a decorative backdrop for the bric-a-brac displayed on the walls.***

***Mitchell provided a glimpse of the color scheme and texture of the adjoining dining room, beginning with the fretwork above the fireplace opening, carved in a leafy pattern and "tinted uniformly with dark Prussian blue, so dark that to some eyes it might pass for black. Add to this the flashing fire-blaze, the gleaming bolt-heads of the frame work, the sheen of the crystalline plates, the scarlet and purple and drabs and gold of the book-backs, the grays and reds and browns and whites and greens of the Japanese vases, and last, the folded richness of the embroidery at the top."***

***Their varied shapes and surface designs added luster and sparkle to rooms throughout the apartment. The chair rail served as a shelf for "plaques, quaint old platters, half blue and white, or a Japanese array of dishes," held in place by a protective brass rod."***

***Ceramic teacups and tankards hung from brass hooks suspended above. The mantel shelf held a selection of five plates or chargers of varying sizes, patterns, and, presumably, origins.***

***The walls of the dining room were compartmentalized into rectilinear sections, with different yet harmonious wall treatments of applied decorative paper or fabric.***

***The old-fashioned mantelpiece was said by Mitchell to take "off the edge of raw New-Yorkism, and in any house at all carrying the traditional sweets of homishness."***

| Dining Room Fireplace in the Bella Apartment home of Louis Comfort Tiffany - New York City |

|

| Fireplace Tile |

***The wreaths of smoke framed picturesque passages of stylized flowers or circular reserves of simple seascapes. Still other areas depicted Japanese vessels, red pottery tea kettles suspended from iron cranes, or decorative blue-and-white chargers arranged on shelves.***

| Painting over fireplace. |

|

| Window screen of eggplants growing on a trellis - Louis Comfort Tiffany dining room - Bella Apartments |

Passing from this dining-room into the sitting-room, we see again a Japanese paper, with a frieze designed by Mr. Tiffany from natural forms after the Japanese style. The walls are paneled with Japanese matting, the panels being small - say, three feet by two - some of them painted by hand, while others show the plain matting, or serve as frames for pictures. A notable marine sketch by Samuel Colman fills one of these places, very quiet in its neutral tone, and carried just far enough to preserve the impression of the scene which the artist designed to depict. The frame is nothing but the narrow molding used to tack the matting to the wall, and exemplifies strikingly the true office of a frame, as Mr. Tiffany conceives it. The usual heavy gilt enclosure would have shut off this picture from all share in "the graceful ease and sweetness void of pride" of its surroundings, and acted as a hindrance, not only to Mr. Colman's charming and self-restrained sketch, but also to the general influence of the apartment.

Here the yellow tone of the walls helps to keep the picture flat, and make it look like a part of the whole side of the room. One feels instinctively that a strong and self-assertive piece of painting, like a Munkacsy, for example, would be out of place here; that its strength would weaken the spirit and temper of its delicate environment; that such a work would suit the hall better, or at least some other apartment than this delcately decorated living-room. To have placed it on the wall, would have been to introduce a blotch or spot of color into an otherwise harmonious scheme. Moreover, to have hedged the Colman about with a huge and intrusive frame, would have been to make a hole in the wall, which is precisely what Mr. Tiffany would have been unwilling to do, a picture, in his view, being not intended to deceive the spectator into the belief that he is looking at a piece of out-doors. It may mystify, to be sure, but never deceive. Mystery is good : to allure the eye to look and not find out, is excellent in art; but to deceive is bad, because the sense of disappointment, after the deception has been discovered, is disagreeable.

The doors in this apartment attract attention at once. They are quite unlike one another, for one thing. The large entrance to the drawing-room, where the usual sliding-doors would have been expected, could door not be so occupied, because of a chimney which would not consent to be penetrated. But a sliding-door was used, nevertheless - only, instead of sliding into the chimney, it slides outside of it, on wheels that run along an iron bar above the entrance-way, acting very much like some barn-doors. It is constructed, for the most part, of small glass panes, and covered by a cheerful curtain of Japanese crape, which can be drawn, or pulled back, at pleasure; and on account of sliding from above, instead of on the floor, there is no groove of brass to trip the passer from one room into the other. The general effect, with the painted wheels, is blue. It is a pretty feature of the room. The door into the hall has two small doors in its center, which can be opened or shut at will, so that one is able to communicate with a visitor on the other side of it, without opening it. The two upright and parallel windows on the same level on the north side have been subjected to a course of treatment by which one of them seems several feet lower than the other, without actually having been cut down. A brass radiator, thrown across the bottom of the left-hand window, makes its sill higher than that of its neighbor; a wide band of glass-work, built across the top of the right-hand window, makes it seem lower than its neighbor. The effort is for irregular balance, as it so often appears in Japanese art; and still further, for special fitness, one of the windows being used to look out of, and therefore needing to be low, while the purpose of the other is to light the room.

|

| Corner in library with horse chestnut leaf-pattern wall covering. |

|

| Corner in library, Bella Apartments. |

| View from library into dining room. |

| Fireplace in library showing Japanese metalwork doors. |

Mr. Tiffany's rooms, indeed, may be considered as an exemplification of these two principles of decorative design, the principle of fitness, and the principle of irregular balance. Illegitimate art, he would say, is art that lacks fitness; in other words, a proper adaptation of means to ends; and decorative art, if it would avoid monotony, must introduce irregular balances.

***End of Sheldon's article***

The Bella apartment was Tiffany's first success in achieving a unified interior-as-work-of-art. The apartment was the subject of much coverage in contemporary journals, some of it likely engineered by Tiffany himself, as a marketing strategy to attract clients for Louis C. Tiffany, Associated Artists, the interior-design firm established in 1881.

An unnamed critic decried Tiffany's intermixing of styles, suggesting that the room would have been more successful "if all the appurtenances were carried out in the same style as the Moorish screen at the entrance." The writer took issue with the Japanese wallpapers and with the "Japanesque feeling in the spider web design on the mica panel on the fireplace." Look for that article in the future.

Click HERE to see a map and description of important buildings(past and present) surrounding the Madison Square area. HERE for more insight into to the square's history - from its time as the center of the world - "...it was in Madison Square that New York's tallest candle glowed and the gaslights glittered brightest." To its less then desirable location - "And then there are the people. They are not splendid like the tulips, and probably not all of them are as reliable like the fountain. They are not employed to sit on the benches for the embellishment of the park, but go there gratis..."

Click HERE to read more about The Fifth Avenue Hotel. Text includes a detailed description of the interior and the social atmosphere. Beginning with the Prince of Wales in 1860, a never-ending procession of the great men of this and other countries had marched through its corridors. The so-called Amen Corner, renowned as the seat of Republican authority in the State, held court for a generation at the world famous hotel.

Delmonico's opened in 1876, it is where the popular dessert the Baked Alaska was created. New York's most popular and elegant restaurant on the park stood at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 26th Street with additional entrances on Broadway and 26th Street. In the early 1900s it was taken over by Cafe Martin, which continued to attract a similar notable crowd. It was on June 25,1906 that Stanford White dined here at the same time as Evelyn Nesbit and her husband Ham Thaw. Later that evening, White would meet his untimely death at the hands of a very jealous Thaw.

wonderful. thank you.

ReplyDeleteThis post is great. Thank you for this post. I like this kind of people who share their knowledge with others.

ReplyDeleteTiffanyFireplace Screen