|

| PENCIL DRAWING SHOWING VESTIBULE CONNECTING WITH 642 FIFTH AVENUE |

|

| FIFTH AVENUE FROM ST. PATRICK'S CATHEDRAL 1890 |

On January 4, 1877 82-year old Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt passed away, leaving an estate valued at more than $100 million. Except for a few million dollars left to family relations and a few bequests to charity, Vanderbilt left his entire fortune to his eldest son William Henry. A year after his father's death he purchased an entire block front on the west side of Fifth Avenue between 51st and 52nd Streets, paying $700,000 for the 150 foot deep site.

|

| CORNER OF FIFTH AVENUE AND FIFTY-FIRST STREET |

The rubbed brownstone facade of William Henry Vanderbilt's mansion was built as a family triple house. The southern half, at the corner of 51st and Fifth, was for William Henry, wife Louisa, and seventeen-year-old son George. William Henry's half of the building measured 80 feet wide and 115 feet deep. The northern half was divided into two parts, to be occupied by two of the Vanderbilt daughters and their husbands - Emily, who had married William Douglas Sloane, and Margaret, wife of Elliott Fitch Shepard.

|

| FIFTH AVENUE AND FIFTY-SECOND STREET |

The architect usually credited with the design and plan for the mansion is John B. Snook, who had designed Vanderbilt's house at 40th and Fifth. However the design of the mansion was probably a collaborative effort of Snook, C. B. Atwood and Christian Herter, both from the interior decorating firm Herter Brothers.

|

| FIFTH AVENUE FRONT OF MR. VANDERBILT'S BROWNSTONE |

The house rested on solid bedrock and was supported by exterior walls that varied in thickness from thirty-six inches to eight inches and by solid-brick interior walls that were at minimum of sixteen inches thick. The first two floors had ceiling heights of sixteen and half feet and the third fifteen feet high.

The Fifth Avenue facades of William Henry's mansion were set back from the street, the property line defined by a low cast-iron ornamental fence that ran along the sidewalk.

There were two symmetrical blocks to the house, with a central courtyard that one entered from Fifth Avenue. A forty-four thousand pound paving stone said to be the largest in America was laid in front of the main entrance.

The roofline was edged by a cornice with stringcourses identifying the three main floors, although there were

actually four stories plus basement. The exterior was enriched by an exceptional amount of decorative carving, in the capitals of the broad pilasters and in panels on the third floor. The house was originally to have been faced with white marble(some say limestone), detailed with red and black marble. Realizing it would take considerably longer to get marble quarried and shipped to the site at the last moment Mr. Vanderbilt instructed his contractor to switch to brownstone. (Besides his advancing age for his reasoning, he let daughter in-law Alva shock New York's architectural sensibilities with her revolutionary limestone combination)

Over six hundred men worked day and night to complete the mansion in a year and a half. Reportedly, sixty sculptors and other artisans were brought over from Europe to create the architectural decorations. Two thirds of the two million spent on the project went into Henry's own fifty-eight-room house. The interiors at 642 and 2 West Fifty-second were more subdued in decor. Old photos show expanses of dark, shiny woodwork, heavily curtained windows, lots of potted palms and gilt-framed pictures, tapestry chairs, Oriental rugs, and damask-covered walls. Each had the obligatory French drawing room in white and gold.

|

| SECTIONAL VIEW OF THE HOUSE |

Although the family moved into the house in January of 1881, it took two additional years to complete all the details of ornamentation and acquire all of the luxurious furnishings. A house-warming reception was given in early March of 1882, with twenty-five hundred invited.

Before entering the imposing atrium the visitor encountered a notice requesting him to touch the electric knob at his left, and to walk in without delay.

One entered the house through an opulent vestibule, thirty-six feet square and one story high, which served as a common foyer for both William Henry's portion and the sections provided for the two daughters. The walls were decorated with mosaics and the ceiling had a large skylight of stained glass in frames of bronze, and with a border of mosaic - a material in which the brownstone pilasters and casings of doors and windows are inlaid.

|

| SKYLIGHT OF VESTIBULE

|

The first object encountered was a colossal, nine-foot-high vase made of brilliant green malachite with applied, gilded allegorical figures representing Fame.

|

THE MAIN VESTIBULE

with the

Demidoff Malachite Vase |

It had been bought at auction by one of William Henry's agents at the sale of the effects of Prince Paul Demidoff, held at San Donato Palace in Florence, Italy, in 1880. The urn was one of a pair made in 1819, and the other stands in the palace of the Czar in Russia. The urns were made in Paris by Pierre-Philippe Thomire, and Czar Nicholas of Russia gave one to Count Demidoff. To the left of the vase was the entrance to William Henry and Louisa's part of the house.

|

| COME RIGHT IN, MR. VANDERBILT IS EXPECTING YOU |

Pushing back the unfastened doors, crossing the mosaic pavement, and, on turning to the left and passing through Barbedienne's reduced copy of Ghiberti's gates finds oneself within the vestibule proper, just as the butler is about to open for him the inner doors of the mansion.

This vestibule, treated in a Pompeian manner, is twelve feet square, surmounted by a flat dome of mosaic, the walls covered with Sienna marble, a stone used also for trimming the paneled bronze doors, one of which opens into Mr. Vanderbilt's private library on the left, another to the cloak-room on the right, and a third to the main hall of the house. The floor is the finest specimen of mosaic made in America.

|

| THE GHIBERTI'S DOOR |

The great doorway, in gilded bronze, was a reduced copy of Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise at the Florentine Baptistry. Michelangelo is said to have declared these worthy of being the gates of paradise.

Atrium

One enters the spacious hall - sixty feet long by forty feet wide - its central part running up to the top of the house, and surrounded by galleries on each story, which are supported by colonnades of red Numidian marble, with bronze caps and bases. Facing the principal entrance is an ornate mantel of the same material with bronze decorations, flanked by two bronze figures. All the doorways into the principal rooms used tapestries as coverings from a set belonging to the Duc de Maine, grandson of Louis XIV.

|

| THE ATRIUM GROUND-FLOOR

|

In this photograph the entrance to the picture gallery on the west is directly ahead, the stairs on the north side are to the right, the door to the dining room on West 51st Street to the left and the opening to the drawing room overlooking Fifth Avenue behind.

|

| THE ATRIUM GROUND-FLOOR

|

|

| PERSPECTIVE OF THE ATRIUM GALLERY

|

The walls are wainscoted twelve feet high in panels of English oak, profusely and elaborately carved, with a frieze embodying a Celtic motive and adorned with small panels of inlaid marble; and the wall spaces, to a height of five feet, are of colored and gilded plaster modeled in relief. A rich parquetry of various woods - American and English oak, and rosewood and mahogany - constitutes the floor, and is partly covered by handsome Turkish rugs, both large and small. The furniture, designed in keeping with its surroundings, was made to order, of carved English oak, ornamented in brass and upholstered in Persian stuffs.

The Drawing Room

The drawing room overlooked Fifth Avenue and measured thirty-one by twenty-five feet. It was located between the library on the north and the Japanese parlor to the south. Its coved ceiling had a mural painted by Pierre-Victor Galland, the French decorative artist who had been Christian Herter's teacher in Paris; Herter had arranged the commission. The elaborately carved doorway frames were encrusted with gold.

|

| DRAWING-ROOM WITH FIFTH AVENUE TO THE LEFT AND THE JAPANESE ROOM AHEAD |

|

| "FORTUNE" - CUPID ON GLOBE OF TURQUOISE, CARVED OUT OF SOLID IVORY |

|

NORTH-WEST CORNER OF DRAWING-ROOM

With Portion of Galland's Fete |

The walls of the room were of carnation-red velvet with applied mother-of-pearl butterflies and gilt applique work of trees whose flowers are made of jewels, and from whose branches hang festoons of gold-thread, which glistened in the gaslights of the chandelier. One awestruck visitor reported that "when the lights are burning, its splendor is akin to the gorgeous dreams of oriental fancy."

|

DRAWING ROOM

With Vista Through The Atrium and Picture-Gallery to the Conservatory

The effect is gorgeous in the extreme : everything sparkles and flashes with gold and color - with mother-of-pearl, with marbles, with jewel-effects in glass - and almost every surface is covered, one might say weighted, with ornament; the walls, with carnation-red velvet, showing profusion of gilt applique work, which represents conventional trees whose flowers are made of jewels, and from whose branches hang festoons of gold thread among which butterflies disport themselves; the frieze, with gilt and mother-of-pearl; the ceiling, with canvas painted by Galland to show a festal procession of life-size knights in armor, falconers, boys, ladies, peasant-women bearing the first-fruits of the vintage, oxen, and horses, all under a sky of pale blue and grays, beneath which the ceiling itself springs in a graceful curve from the frieze-line, while slender, painted columns run up and carry a trellis motive to the center.

|

|

| A CORNER IN THE DRAWING-ROOM |

Two luxurious divans, covered with a design in raised cherry velvet on a ground of yellow satin, so that the design looks like a lace thrown over the ground, occupy two corners of the room. Some of the smaller chairs are upholstered in rich Chinese embroideries, the woodwork being gilt. The lighting of this splendidly embellished and bedecked apartment has been beautifully thought out. So managed that the gas-jets suffuse a mild and gentle radiance. At each of the door-jams, and at the bay-window, stand columns or pedestals of onyx ornamented with bronze; upon these are set the gas-fixtures in the form of vases made of open-work of bronze, the spaces filled in with colored glass, behind which are the burners, and above the rim of each vase a corona of gas-jets heightens the brilliancy of the effect.

|

| Ormolu-mounted lapis lazuli-inset and etched onyx pedestals |

Click HERE for a interesting story on these columns from the drawing-room.

|

PORTION OF THE "FETE"

Painted by Galland

|

The scene in the drawing room represented a festive procession of knights, ladies, and their peasant entourage bringing in the first grapes of the harvest. Some years later Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, in their book The Decoration of Houses, included a passage which reveals that Herter and Vanderbilt were re-creating in the drawing room of a Fifth Avenue mansion what they had seen in ancient Old World palaces; the authors noted that in many old Italian prints and pictures there are representations of these saloons, with groups of gaily dressed people looking down from the gallery.

In Italy the architectural decoration of large rooms was often entirely painted, the plaster walls being covered with a fanciful piling-up of statues, porticoes and balustrades, while figures in Oriental costume, or in the masks and patti-colored dress of the Comedie ftalienne, leaned from simulated loggias or wandered through marble columns.

|

| CORNER OF DRAWING-ROOM |

|

A PORTION OF FRIEZE AND CEILING

Drawing-Room

|

|

THE DRAWING-ROOM

Looking into the Library |

The Library

The library(17' by 26') at the northeast corner of the building, adjoined the drawing-room. With rosewood trimmings, inlaid with brass and mother-of-pearl, and carved to utmost elaboration over the doors and in the mantel. Of rosewood also, similarly inlaid, is the costly furniture that lends its quiet cheer to the general tone of dull olive-green. The ceiling decoration, of richly-molded plaster-work with innumerable little beveled mirrors, sparkled in the light.

|

| THE ANTE-ROOM TO LIBRARY

|

The Ante-Room or private reception-room was entered off the vestibule and was connected to the library. It was paneled in mahogany and stamped leather.

In the library every item contributed to the richness of decor, whether builtin bookcases, furniture such as the library table, walls that were hung with blue-green plush on a gold ground, or the innumerable bibelots. Mother-of-pearl ornamentation was skillfully worked into the surfaces of the cornice, pilasters, and bookcases. Especially striking is the use of mother-of-pearl; very rarely, if ever, in the history of house decoration has this material been used so generously. The pattern of the wallpaper in the library was repeated in the fabric of two of the upholstered, tasseled chairs.

|

THE LIBRARY SOUTH-WEST CORNER

The various objets d'art seen throughout the room were chosen by William Henry and Louisa themselves. These objects often had interesting histories, as with the folding fan (seen on the bookcase) reportedly owned by Marie Antoinette. The fan leans against one of William Henry's most famous paintings, Jean Leon Gerome's Reception of the Duc de Conde at Versailles.

|

|

IN THE LIBRARY

Portieres of Door Communicating with Drawing-Room |

|

| CHIMNEYPIECE IN THE LIBRARY |

The fireplace is framed in African onyx, a stone much more beautifully colored and veined then the better-known Mexican onyx.

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S LIBRARY |

This room is an archetypal example of the Aesthetic Movement room, the theory behind which is that if a single object is of high aesthetic merit, then a whole room full of such things would provide an even richer experience. The Aesthetic Movement room was an eclectic hodgepodge, in contrast to the so-called period room or culture room which was dominated by the style of one single era or culture, such as Louis XV, Queen Anne, American Federal, Japanese, or Moorish.

|

| LIBRARY TABLE |

The library table was created in 1881 by artisans employed by Herter Brothers. Into the polished rosewood surfaces of its end supports have been worked, in mother-of-pearl inlay, global designs showing North and South America on one end and Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia on the other. The top has a celestial display, with the stars arrayed as they were on 8 May 1821, the date of William Henry Vanderbilt's birth. The carving includes lion's paws and palmettes and echoes the carving found in the paneling of the room.

|

| DOOR LEADING INTO ATRIUM FROM THE VAULTED VESTIBULE |

Mr. Vanderbilt's private room opens from this library, and communicates also with the smaller vestibule of the house, so that the visitor can be shown directly out, instead of being taken into the hall. The woodwork is of carved mahogany, and the ceiling too. Bookcases project from the walls on brackets, in such a way that seats are built in below them. The window is partly hidden by a handsome screen of carved wood with panels of stained glass, and the walls are hung with bluish-green plush on a ground of gold. All the furniture is heavy and ornate.

The Japanese Room

South of the drawing room was a Japanese room. Commodore Matthew Perry's "opening up" of Japan to trade and cultural exchange in 1854 had piqued the Western world's interest. Christian Herter was among the earliest of decorators to take inspiration from the arts of Japan.

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S JAPANESE ROOM |

This room forms the corner at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-first Street(17' by 26'). The furniture and woodwork are of cherry, stained and enameled to look like red lacquer; the walls are hung with Japanese gold brocade up to the frieze line, showing panels of embroidery at intervals, and along them are seen cases of the same wood, similarly treated, which form a multitude of little cupboards and shelves, filled with the rarest objects of bijouterie and vertu.

|

| JAPANESE PARLOR LOOKING INTO DINING_ROOM

|

|

| CHIMNEYPIECE IN THE JAPANESE_ROOM |

|

JAPANESE PARLOR

North-West Corner

|

The ceiling treatment begins at the frieze, and consists of a background of interlaced bamboo, decorated with beams and brackets of red lacquered wood, forming a truss. Uncut velvet of rare Japanese designs and manufacture covers the furniture, while the hangings are of Japanese stuff wrought into fantastic patterns. The carpet, which hides every nook and cranny of the floor, was woven in one piece in England. Very artistic and beautiful are the bronze landscapes with figures that act as doors or sides to some of the little cupboards on the walls.

|

| THE JAPANESE NORTH-WEST CORNER |

|

VIEW IN THE JAPANESE ROOM

East End |

Few rooms decorated in the Japanese mode could approach the one that Herter Brothers helped William Henry Vanderbilt assemble in his new house on Fifth Avenue.

Dining Room

Directly west of the Japanese parlor is the dining-room, about forty-five feet long by thirty feet wide. All around it, forming a wainscot about twelve feet high, are cupboards and cabinets of English oak for holding glass and silver-ware, the series being interrupted on one side by the sideboard, on the opposite side by the windows on Fifty-first Street, and on the west side by the mantel. From the frieze-line starts the ceiling, with heavy wooden ribs, between which appear panels in low-relief representing flowers and fruits, and glazed in transparent colors over a gold ground. A large canvas occupies the center ceiling, surface about twenty feet long by fifteen feet wide, directly over the table, displaying, a hunting-scene in the olden days of France.

|

MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S DINNING-ROOM

|

|

DINING-ROOM

West End |

|

THE FALCON HUNT

Ceiling in the Dining-Room |

Ceiling executed in Paris by E. V. Luminais. Two other hunting-scenes, by the same artist, fill the spaces formed at either end of the room by the arching of the ceiling. The walls were covered with wood panels, generously carved with delicate Renaissance ornament-figures of little children, garlands of flowers and fruit, and horns of plenty. The dark-stained, carved English oak chairs were covered with stamped red leather, relieved with gold.

|

| BUFFET IN DINING-ROOM

|

It was written that Grinling Gibbons would have to "hide his diminished head" before these carvings. Filled with a notable porcelain collection.

|

| FIREPLACE AND PORTION OF BUFFET |

|

| DINING-ROOM SIDE CHAIR |

Click HERE for more on this chair.

|

| DINING-ROOM EAST END |

For more on the Dining-room click HERE. A set of four chairs sold in the 1990s for $99,000.00.

|

| VIEW IN THE PANTRY |

Behind the dining-room is the butler's pantry, wainscoted two stories high (with a gallery all around it) in a succession of cupboards for different purposes, their doors made of ash, with panels of curled maple woods that compose, also, the paneling of the ceiling. The floor is tiled. All the modern conveniences that were known or could be invented are introduced into this useful apartment. There are safes for the silver, telephonic communication with the Grand Central Depot, the livery-stable, and Mr. Vanderbilt's private office, the usual messenger, police, and fire calls, and other conveniences. The butler's pantry directly connected with the servants' stairs, the main hall (and thence with the front door), the dining-room, and the entrance on Fifty-first Street.

Stairway

At a distance of some twenty feet to the right of the front door the magnificent staircase discloses itself. This staircase, on the wall-side, continues the English oak paneling of the hall; the broad rail is supported by carved uprights of the same wood, and covered with a red velvet cushion, the spaces between the uprights being occupied by a rich scroll-work of bronze which, at intervals, clasps balls of red African marble.

|

| Looking up the Well of Staircase-View of the Vertical Perspective |

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S STAIRCASE |

The grand stairway to the upper floors made its way around an atrium that was open from the first floor to the top of the fourth, a light-well that illuminated the inner parts of the house. Sixty feet long by forty feet wide, its central section surrounded by galleries on each story, which are supported by colonnades of red Numidian marble with bronze caps and bases.

|

STAIRCASE

With Lampidiere by Noel

|

The stairway contained a superb newel with a life-size bronze figure of a girl, whose left arm encircles a massive urn, her bracelets, belt, and head-dress being of cloisonne enamel sparkling with jewels, while out of the urn grows a lantern of intricate bronze work.

|

| FIRST LANDING |

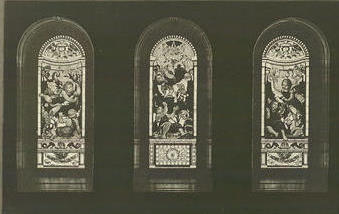

At the main landings of the stairway were stained-glass windows designed by La Farge. On the first landing they depicted the fruits of commerce, an allegory showing ships and railroads upon which the Vanderbilt fortune had been founded.

|

COMMERCE BY LA FARGE

Stained Glass Designed by Lafarge |

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S HALL COLONNADE SECOND STORY

|

Surrounding the walls were a set of six tapestries commissioned by Louis XIV as a present to the Landgrave of Hesse. Theme was taken from Honore d'Urfe's "L'Astree".

|

| SCENE FROM DURFE'S L'ASTREE

|

At the second-floor landing the windows represented hospitality and prosperity.

|

| HOSPITALITY |

|

GALLERY

Third Floor of the Atrium

|

On the third floor landing is illustrated the myth of the Golden Apples of the Hesperides – the last and most difficult of Heracles’ 12 tasks.

These windows were removed in 1890 by Edith Vanderbilt and shipped to Biltmore. They remained in storage until one of them - that of the middle level, depicting hospitality and prosperity was placed on display at the Biltmore Legacy center in Antler Hill Village, the new entertainment, dining and shopping green on the estate.

|

| ATRIUM GALLERY-THIRD FLOOR |

Bedrooms

On the second floor, are situated Mrs. Vanderbilt's boudoir, bedroom, and dressing-room, Mr. Vanderbilt's bedroom and dressing-room, Mr. George Vanderbilt's library and bedroom, and a guest's bedroom and dressing-room. The hall on this floor is a gallery, surrounded by a colonnade of red African marble treated similarly to that below. A pair of very heavy embroidered Japanese portieres of an old gold ground, hang before the double doors that lead into Mrs. Vanderbilt's beautiful bedroom, the furniture and embellishments of which were made in Paris expressly for the purpose by the internationally known decorating firm of Jules Allard and Sons.

|

| MRS. VANDERBILT'S BEDROOM |

The wood-work and furniture consist of various polished woods with inlays; the bedstead being of mahogany with rosewood trimmings, and draped in the French manner by a canopy (just below the ceiling) of brocaded silk of Louis Seize designs of sprays and flowers on a buff ground, framed in with broad bands of cherry velvet, and richly trimmed. The same material covers the walls, and serves as hangings for the windows, while against the windows themselves are curtains of rich Venetian white lace. The Dutch carpet, woven in one piece, has designs in blue and green on a red ground, and each article of furniture was specially prepared to harmonize with the woodwork of the room, which is Louis Seize marquetry - mahogany inlaid with diverse light woods. The portihes chair and lounge covers, and bedspread, are choice specimens of Venetian, Dutch, and Eastern embroideries. The recessed balcony, with its gold mosaic ceiling and bronze railing, was accessible through windows that overlooked the Elgin Botanic Garden.

|

| FIFTH AVENUE FACADE SHOWING BALCONY |

|

| "DAWN" |

For the ceiling of Louisa's room her husband had bought a large painting by Jules Lefebvre, representing the nude figure of Aurora "seated in a chariot, drawn through the air by two young women of pleasing mien and manner".

To the right a door opens into Mrs. Vanderbilt's dressing-room, which is fitted up in mahogany, with a spacious dress-closet of ash at the back. To the left is an entrance to her boudoir, which occupies the northeast corner of the house.

Twenty-six feet long by eighteen feet wide, its tone of blue from the walls hung in silk brocade shot with gold-thread, from the ceiling painted with panels of figure-subjects, from the furniture upholstered in stuffs similar to that on the walls and at the windows. The carved, ebonized mantelpiece has many shelves and cupboards filled with rare bric-a-brac, and a fire-opening faced with Mexican onyx.

|

| MRS. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S BOUDIOR |

|

BOUDOIR

Second Floor - North- East Corner

|

|

| CHIMNEYPIECE IN BOUDOIR |

To reach Mr. Vanderbilt's bedroom, at the southeast corner of the building, you would pass through Mrs. Vanderbilt's bedroom and dressing-room, along the Fifth Avenue front, or into the hall.

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S BEDROOM |

A general sunshiny effect of golden yellow predominates in this apartment. The ceiling and frieze are painted in hand and stencil work, with many medallions of figures representing sportive Cupids, and the tapestry paper of the walls is partly hidden by five or six oil paintings. Bedstead, bureau, wardrobe, cabinet, lounge, and chairs are of rose-wood, intricately inlaid with satin-wood, mahogany, and maple. The draperies are of pale blue.

Mr. Vanderbilt's dressing-room, opening from this place, is treated in Pompciiau Style, especially as respects the fantastic color-scheme of the decorated segmental barrel-arch of the ceiling, and the figures of women and mischievous Cupids at intervals along the frieze - the whole hand-painted on canvas. The bath-tub(silver), closets, and washbowls(silver) are all screened behind mahogany sliding doors, which have long mirrors on their faces, and the inside walls and ceilings are lined throughout with glass tiles, which also cover the other walls.

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S BEDROOM |

The library of Mr. George Vanderbilt is a comparatively plain room, whose walls are lined with mahogany bookcases ten feet high, upon which stand busts and vases, the ceiling being paneled in the same wood, and the wall-spaces concealed by a dark, rich leather paper.

|

| GEORGE VANDERBILT'S LIBRARY |

|

| VIEW ON THE UPPER LIBRARY |

The only guest-room on this floor was originally intended for Miss Vanderbilt before she became Mrs. Webb. Furniture of rosewood, its door-casings of the same inlaid with mother-of-pearl, its walls of gold brocade, and its ceiling decorated to carry out the golden scheme of the surroundings; and still more charming is the dainty and ornate dressing-room of satinwood, its closets, bathtub, and wardrobes lined with Mexican onyx, and screened by sliding doors whose faces are mirrors that reach down to the floor; its walls decked with beveled mirrors to a height of eight feet, while the space above, together with the entire ceiling, is covered with a paneling of small mirrors upon which have been painted lacework patterns through which, here and there, a saucy young Cupid has burst his way. Curtains of Venetian point-lace partly conceal the windowpanes, an Eastern rug reflects its sober radiance from the floor, and the general effect is that of a Marie Antoinette dressing-room in the palace of Fontainebleau.

The Art Gallery

Passing from the main hall through a deep archway of American oak stained black, with panels and carvings of mahogany in anticipation of the work above, the scheme being to keep the ebonized wood below, so that nothing shall disturb the pictures, and thence to proceed up to the bright coloring of the mahogany of the ceiling, where the black is in lines only, the copious decorations being arabesques on mahogany. Directly over the archway is situated a gallery for musicians. Behind the pictures the walls are covered with tapestry of a dull-red tone, and above them are painted in unobtrusive arabesque designs. The parquetry floor, mostly concealed by a rug woven in one piece, shows an outer border of mosaic. Two large divans richly carved, upholstered in Eastern stuffs, constitute, with the table, the principal furniture.

|

VIEW OF GALLERY, MAIN ENTRANCE

With Perspective of Atrium and Drawing-Room

This gallery contained one of the most notable private collections of modern pictures in the world.

|

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S PICTURE GALLERY |

|

| THE PICTURE GALLERY |

|

| MR. WILLIAM H. VANDERBILT'S PICTURE GALLERY

|

|

The Picture-Gallery

|

On the first floor, one entered the huge art gallery (thirty-two by forty-eight feet, thirty feet high) through broad archways directly west of the hall. The space was divided into a larger room and a smaller one, and the walls were covered with a dull red fabric and had mahogany architectural trim. Above, the skylight was composed of opalescent and tinted glass.

When the Vanderbilt's needed a ballroom , the rug and furniture were removed. By opening the doors to the musicians loft , music could be heard throughout the house. By night, 169 gas jets blazed away for illumination.

|

VIEW IN THE GALLERY

Click HERE for a private tour and review with a

complete catalogue description of the holdings of oil paintings and watercolors of the Vanderbilt Art Gallery as it existed in December, 1883. |

|

| VIEW IN THE GALLERY |

|

VIEW IN PICTURE-GALLERY

With Fifty-First Street Vestibule |

Adjoining the Gallery was a Watercolor-Room, treated in Moorish fashion, and entered from the landing of the main staircase. It had a sky-light of stained glass, and was surrounded by a narrow gallery which overlooked the principal picture-gallery, and had a railing of spindle-work in black cherry. The upper part of the walls were covered with a dull-red velvet; the lower part with tapestry of the same tint. Divans and chairs were placed at either end of the room.

Major changes were started a year after Vanderbilt moved in. The Watercolor-Room was replaced, creating a 150 foot vista from the windows of the Drawing-room through the hall and gallery(now 55' by 35') to the walls of a new, glassed-in garden(accessed by removing a fireplace). On December 20,1883 Vanderbilt invited 2500 men from the world of business and art to inspect the galleries and tour the house.

By cards of invitation the public was admitted to the gallery through a special door on 51st Street, between 11:00 A.M. and 4:00 P.M. on Thursdays, but because the they behaved so badly, this practice was stopped after a couple of years.

The Conservatory adjoined the Gallery to the west, the dimensions being thirty-six by twenty-two feet. Entering in the center you were surrounded by abundance of ferns, palms, and tropical plants, in a high degree of moisture, heat, and carbonized atmosphere. The walls and ceiling are covered with tiles, the floor is laid in Roman scagliola and, by means of some sliding-doors, the Conservatory can be thrown open to form an alcove of the picture-gallery.

|

| PORTION OF THE CONSERVATORY |

As beautiful as all of this was considered to be, it exemplified, the very archetypal superabundance of ornamentation against which later generations of modernists and minimalists rebelled. William Henry was so proud of the house he had built and the rooms he had furnished that he paid for the publication of four large volumes on the mansion.

Critics expressed amazement for the interiors but panned the exterior as something akin to "brownstone packing boxes" or a "gigantic knee-hole table".

From the American Architect & Building News -"Mr. William H. Vanderbilt's building plot - is the whole "block " from Fifty-first to Fifty-second Street, on the western side of Fifth Avenue, and one hundred feet deep. On this there are now going up two houses in brownstone, from the designs of Herter Brothers, the decorators. One of Mr. Vanderbilt's sons is building, on the north-west corner of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-second Street, a house in gray limestone, of which Mr. Hunt is the architect; and another, at the north-west corner of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-seventh Street, a house in the same gray limestone and red brick, of which Mr. Post is the architect.

In size and cost, these Vanderbilt houses arc the most" important" dwellings which have been built in Now York since the "palatial mansion " in white marble of Mr. Stewart, which probably cost more than any two of the Vanderbilt houses, and possibly as much as all four. That edifice, however, of which the late Mr. Kellum was the designer cannot be said to possess any architectural interest; whereas so little cannot be said without qualification of any of the Vanderbilt houses.

Without doubt it comes nearest to being true of the two brownstone houses. These are nearly square in plan, and although there are variations in detail, and even in arrangement, these variations are trivial, and the houses are so nearly duplicates that to describe one is virtually to describe both. Each consists of a very slightly recessed centre and wings, which latter carry a blind attic, or solid balustrade, while the centre stops with the cornice over the third story. The ground floor has square-headed openings in the wall, neither grouped nor symmetrically spaced, and the jambs and lintels are unmodelled. The wall at two-thirds the height of the openings is divided by a line drawn arbitrarily, that is, with no reference to any constructive feature of the building. Below this line, the wall is rubbed sandstone. Above, it is covered with carved vines and vineleaves, not arranged in patterns nor conventionalized, but treated with complete naturalism. This carving is stopped against the openings by dwarf pilasters of the same height with the band of foliage, but these do not occur at the outer angles of the wall, where the carving simply ceases at an inch or two from the edge. Over this is a taller story reinforced with doubled pilasters at the angles, and with single pilasters between the openings. The openings of this story also are square-headed, but unlike those of the first story, which arc merely holes in the walls, they are covered with developed lintels which are carved in foliage, treated naturalistically like that below.

Over this is a shorter story, composed of round-arched openings with very narrow archivolts, grouped over the wings, and separated by pilasters which extend almost to the edges of the openings. At the angles the openings encroach upon the lines of the pilasters in the story beneath. Through the middle of this upper story runs a very wide and deeply cut frieze, of foliage arranged in patterns and conventionalized in the Roman manner. Over this story is an entablature with a convex frieze, which is not decorated, and a cornice crowned with antefixce of lions' heads, apparently in terra-cotta, and meant to be gilded. Over this, at the wings, is the blind attic already described. There is no visible roof.

It is curious how so much good work as these buildings show can be so ineffective. The material, a very dark, almost black, Connecticut brownstone, which has been almost discarded for many years by reason of its friableness and tendency to rapid decay, is against the effect of the buildings, but the design is still more unfavorable. In strictness, neither building exhibits an architectural design. The essential trouble is that neither is properly a building. There are no features, there is no relation of parts, there is no development of masses or lines, vertical or horizontal, there is no arrangement of openings with reference to each other.

The angles of the buildings, emphasized and reinforced by the pilasters in the second story, are cut to pieces in the first by carrying the unframed carving to the angle of the wall, and in the third by interrupting the lines of the pilasters with the openings. The carving throughout is well, sometimes exquisitely cut, and carefully modelled. The foliage of the first story is remarkably good in execution, but das macht nichts. It has nothing to do with this building, nor indeed with any building. It is not architectural decoration. It is not designed with reference to its place and function, and so does not help the expression of the wall. It is not framed, and so directly injures tho expression of the wall it is meant to decorate. The belts are framed at one end by the preposterous dwarf pilasters, but above and below they are not framed at- all. One wonders what the designer imagined that mouldings were invented for. The wide frieze of the third story is well carved, and the carving is well calculated for its distance from the eye; but this makes nothing either. It is not better in its place than it would be in any other place. Meanwhile the upper frieze, which is framed, and in which this enrichment would have been suitable, is left entirely bald. Nowhere, except in the pilasters of the second story, is there an effort to develop and enrich the constructive features of the building. In truth, the justly disesteemed Stewart mansion itself is more properly than this an architectural design, seeing that its parts bear more relation to each other and to the whole, and that its architecture could be less readily removed without injury to the building as a building. These are merely boxes of brownstone with architecture applique, and the only interest they have is the precision and delicacy of some of the detail taken by itself. How much this detail would gain by being put in the right place and designed with reference to its place may be judged by comparing these houses with the house in upper Fifth Avenue, designed by Mr. Clinton, of which I have heretofore spoken, where the carving is not better in itself than this, and certainly not more profuse, but where it is bestowed with reference to the building, instead of occurring promiscuously along the wall. If these Vanderbilt houses are the result of entrusting architectural design to decorators, it is to be hoped the experiment may not be repeated." Published in 1881. DED when were you born? :)

Kitchen and Servant Quarters

The kitchen and men's servants quarters were in the sub-basement, the women's servants quarters were in the attic.

The Stables

The stabling for 640 Fifth Avenue was located at 49 East 52nd Street. Two-story stone structure divided into three principal stables. Had a sky-lighted courtyard in which the horses could be exercised in any weather.

|

| STABLE COURTYARD |

|

| COACH-HOUSE |

The stabling consisted of twelve box-stalls for Vanderbilt's high-strung trotters. Six ordinary stalls accommodated the heavier coach-horses.

|

| STABLE |

William Henry Vanderbilt died on 8 December 1885, not quite five years after moving into his new mansion. Reportedly he was the richest man in America. His will stated that the house was to be Louisa's for her lifetime and then pass to their youngest son, George. George was forbidden by the terms of the will to sell the property.

|

| This photo reflects the alterations done by Frick when leasing home. Note the new front entrance and now enclosed open balcony off Mrs. Vanderbilt's original bedroom. Date sometime after 1911 when NYC widen Fifth Avenue forcing owners to remove the ornamental fences that fronted their homes. |

By 1905 George was in financial straits because of enormous debts incurred with the development of his Biltmore estate, and rented 640 Fifth Avenue to Henry Clay Frick on a 10-year lease. Frick used the house while waiting for the completion of his Carrere & Hastings designed mansion at 70th Street and Fifth Avenue.

When George died in 1914 the mansion passed to Cornelius III, son of George's oldest brother, Cornelius II, and grandson of William Henry. Cornelius III had scandalized the family and Society by marrying Grace Wilson. Grace undertook a largescale renovation with the aid of architect Horace Trumbauer, transforming the interiors into "period rooms" of the time of Louis XV. By 1927, as commercial establishments increasingly moved into Fifth Avenue the northern half of the mansion-the part originally inhabited by two of William Henry's daughters and their families was torn down to make way for a department store. Just before his death in 1942, Cornelius III sold the remaining portion of the property, William Henry and Louisa's side to the William Waldorf Astor estate, who wanted to developed the site. It was demolished in 1947. Two years earlier a great sale was held at the house. Paramount Pictures purchased several of the rooms to be used as movie sets. The Crowell-Collier Building replaced Vanderbilt's Triple Palace.

***Look for future post - "The Black Hole of Calcutta" 640 Fifth Avenue***

Early in Williams life the Commodore thought his son slow witted and often referred to him as a "good for nothing" and "Beetlehead".

The family is shown in the parlor of the Vanderbilt residence at Fifth Avenue and 40th Street. William Henry is seated at the left. Beyond him stands Frederick, behind his mother, Maria Louisa; then young George (the futurebuilder of Biltmore), and next are Florence and William Kissam (builder of Marble House at Newport), then fourteen-year-old Lila, seated at the table. Margaret is standing with her back to the viewer while Elliott Fitch Shepard (Margaret's husband) has his coat removed by a servant. Emily is wearing a white gown and standing before her husband, William Douglas Sloane who is seated next to Alice, who is married to the man standing at the far right, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, the head of the family in the next generation and the builder of The Breakers at Newport.

660 Fifth Avenue at the north west corner of 52nd Street was the William K. Vanderbilt house.

North east corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street, 657 was the mansion of Mrs. Anne Lohman(wife of "Doctor" Lohman) who was known professionally as Madame Restall.

At 653, south east corner, was the Morton F. Plant house.

In the middle of the block stood 647 and 645 known as the "Marble Twins".

In 1901 the Union Club built a clubhouse at 641, northeast corner.

St Patrick's Cathedral, started in 1858, stands at the south east corner.

The land that is now Rockefeller Center, on the south west corner, was once the Elgin Botanic Garden, established by Dr. David Hosack, the physician who attended Alexander Hamilton after his fatal duel with Aaron Burr. The Lewis and Clark expedition sent plants here for identification.

Far removed from the center of population at the tip of Manhattan, the area surrounding Fifth Avenue between 42nd Street and the southern end of Central Park remained rural in character well into the first half of the nineteenth century. Most of the territory was originally owned by the City of New York, which had been granted “all the waste, vacant, unpatented, and unappropriated lands” under the Dongan Charter of 1686. The city maintained possession of these common lands - which once totaled over one-seventh of the acreage on Manhattan - for over a century, only occasionally selling off small parcels to raise funds for the municipality. The city’s policy changed after the American War of Independence. In 1785 the Common Council commissioned surveyor Casimir Teodore Goerck to map out five-acre lots to be sold at auction. A new street called Middle Road, now known as Fifth Avenue, was laid out to provide access to the parcels. A second survey of additional lots was undertaken by Goerck in 1796 and two new roads, now Park and Sixth Avenues, were created. Under the city’s plan, half of the lots were to be sold outright while the other half were made available under long-term leases of 21 years. Many of the parcels were acquired by wealthy New Yorkers as speculative investments in anticipation of future growth in the area. A number of public or public-minded institutions also purchased or were granted large plots along the avenue; the Colored Orphan Asylum was located between 43rd and 44th Streets, the Deaf and Dumb Asylum on 50th Street just east of Fifth Avenue, the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum between 51st and 52nd Streets, and St. Luke’s Hospital between 54th and 55th Streets. The rough character of the neighborhood—other tenants at this time included Waltemeir’s cattle yard at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 54thStreet—persisted into the 1860s, when development pressures finally began to transform the area into a fashionable residential district.The inexorable northward movement of population and commerce along Manhattan Island picked up momentum during the building boom that followed the Civil War. Four-story brick and brownstone-faced row houses were constructed on many of the side streets in the area, while larger mansions were erected along Fifth Avenue. Pioneers in this development were the sisters Mary Mason Jones and Rebecca Colford Jones, heirs of early Fifth Avenue speculator John Mason and both widows of established Knickerbocker families. In 1867, Mary Mason Jones commissioned a block-long row of houses, later known as the “Marble Row,” on the east side of the avenue between 57th and 58th Streets. Two years later in 1869, her sister hired architect Detlef Lienau to design her own set of lavish residences one block to the south. Having established the area as an acceptable neighborhood for the city’s elite, other wealthy New Yorkers soon followed the Jones sisters northward up Fifth Avenue. The gentrification of the area was further motivated by a number of important civic and institutional building projects initiated in the mid-nineteenth century. Most notable was the planning and construction of Central Park in the late 1850s and 1860s; the preeminence of Fifth Avenue as the fashionable approach to the park was later solidified in 1870 when the city created a monumental new entrance at Grand Army Plaza. A number of eclesiastical organizations also opened impressive new buildings on the avenue at this time; St. Thomas Episcopal Church at 53rd Street in 1870, the Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church at 48th Street in 1872, the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church at 55th Street in 1875, and the Roman Catholic St. Patrick’s Cathedral between 50th and 51st Streets in 1879. The status of the area as the city’s most prestigious residential neighborhood was firmly cemented in 1879 when the Vanderbilt family began a monumental house-building campaign on Fifth Avenue. William Henry Vanderbilt - the family patriarch since the death of his father Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1877 - sited his own palatial residence on the western block front between 51st and 52nd Streets, while his two eldest sons each erected mansions just to the north. The scope of the work was so impressive and the influence of the family on the neighborhood so great that the ten blocks of Fifth Avenue south of Central Park came to be known as “Vanderbilt Row.” By the turn of the twentieth century, however, the march of business up Fifth Avenue had progressed such that the Vanderbilt's were engaged in a constant struggle to protect their enclave from unsympathetic commercial redevelopment.

Sources: I'm not a writer or a scholar. Most of the text is lifted, paraphrased, combined and/or changed from a number of sources. All the color plates are from the Holland Edition of Mr Vanderbilt's House and Collection. Published in 1883, a one thousand, ten volume edition as compared to Mr Vanderbilt's first four volume commission. Black and white photos are from the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian. All from 1883. Main source of text is from the Holland copies, Artistic Houses 1883 printing and the 1987 Dover Publication reprint. Additional information taken from Gilded Mansion: Grand Architecture and High Society and The Vanderbilt's and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations, 1879-1901. I've taken out most of the flowery phrases and kept the pertinent descriptive text. If you have additional information or corrections please post a comment.