|

| As the new While House would look from Pennsylvania Avenue. The centre is the present building, the columned wing on each side being the proposed additions |

THE FUTURE OF THE WHITE HOUSE

By COLONEL THEODORE A. BINGHAM, U. S. A.

|

| Elizabeth K. Monroe |

|

| Louisa Catherine Adams |

SOME day the present White House will have to

|

| Sarah Yorke Jackson |

|

| Emily Donelson |

postponed as long as it has been. But there is some consolation in the fact that the question has recently come in such a way that it is sure to command the attention of the country within a very few months.

The awakening of interest in the enlargement of the White House was brought about by the action of a Centennial Committee composed of Senators, Governors and other prominent and representative citizens from all parts of the country. A meeting was held in Washington last February, and plans for celebrating the end of one century and the beginning of another at the National Capital were discussed. It was the general sentiment that there should be some permanent mark established in Washington to commemorate this epoch in our history. Several suggestions were made and discussed, and in the final report the Committee on Permanent Memorial suggested the extension of the White House to meet the demands of the present time.

|

| Mrs. Robert Tyler |

During her occupancy of the White House the late Mrs. Benjamin Harrison took a great interest in this subject and studied it carefully, being assisted by the advice of competent persons, and especially of the Engineer Officer then in charge of Public Buildings and Grounds, and by the talented architect elsewhere referred to. As a result, plans were drawn which, while susceptible of some improvements, may confidently meet honest criticism in all respects. These plans are herewith presented.

WHITE MARBLE SHOULD BE USED FOR EXTENSION

THE material used for the extension should be white marble, as this will preserve the historic color and will match the original building, which must always be kept painted in order to preserve it. The extensions should be as nearly fireproof as possible, and all points of construction should be the best taught by modern science.

At the same time care should be taken that, while the home of the American President should comport with the dignity and greatness of his high office and the wealth and power of our nation, its elegance should yet be simple and enduring. Nothing demands that this house should exceed in richness of detail or wealth of decoration the homes of all other citizens of the Republic. On the contrary, it should just meet that middle line between dignified elegance and unnecessary display which will excite the respect (even if unexpressed) of the foreigner and satisfy the common-sense of the mass of the American people.

THE PRESENT BUILDING SHOULD BE KEPT INTACT

IN THE plan for building a new house for the President elsewhere than on the present site it has been proposed to utilize the present mansion for offices. One plea therefor has been that the historic building should be left as it is. This is certainly to be insisted on. But it is said the mansion is too pure a piece of architecture to be marred by additions. This, however, is a specious argument, since the original design contemplated side additions, and if the building in its present state were used as offices it would be wrecked in five or six years. Those who have no experience with public buildings, or with this building in

|

| Martha Johnson Patterson |

the whole interior of our historic Executive Mansion would be not only a very expensive matter, but would fail to meet the requirements of the case, and also, it is believed, the approval of the country at large.

To live in the White House has been held up to the ambition of every schoolboy for a hundred years, and our people would hardly, if ever, entertain the idea of having the President live elsewhere. Let a summer house be built somewhere else, perhaps, but there is really no good reason why the home of the President should, for another Century, if ever, be removed from the house and the site so close to the hearts of the people.

Conversation with hundreds of visitors from all parts of the country has revealed an overwhelming preponderance of sentiment in favor, under all circumstances, of preserving intact the present structure, no matter what plan may finally be adopted for the greater accommodation of the President's private life and official work.

SPECIAL ADVANTAGES OF MRS. HARRISON'S PLANS

Mrs. Harrison's plans would involve a minimum of disturbance of the present conservatories now attached to the mansion — only one section requiring to be moved until the final completion of the entire plans, when all the conservatories are finally removed to their location in the general plans.

It is certain that the carrying out of Mrs. Harrison's plans would give America perhaps the most delightful house for private and official life of any Chief Executive in the civilized world.

Some may ask, what are the special advantages of Mrs. Harrison's plans? They are, to my mind, briefly these : The official and private ends of the mansion are kept separate, as now, avoiding all confusion of moving and of refitting and modernizing the present private apartments — a very expensive matter owing to the peculiar construction of the present building.

Mrs. Harrison's Plan

By 1889, Mrs. Caroline Scott Harrison had decided that the White House should be expanded in a grand manner to include an executive wing and a museum wing.

Mrs. Harrison worked with architect Frederick D. Owen to create a plan to expand the White House on the east and west sides and build a new conservatory on the south side, creating a large courtyard in the middle. The plan was rejected by Congress, and the Harrisons instead renovated the mansion with electricity and other modern conveniences.

On December 12, 1900, the City of Washington celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary as the seat of the federal government and the home of the president. The centennial of the first occupancy of the White House by President John Adams was observed with a great reception at the White House, a parade to the Capitol and observances by both houses of Congress. A centerpiece of the White House reception was a large plaster model of the plan.

|

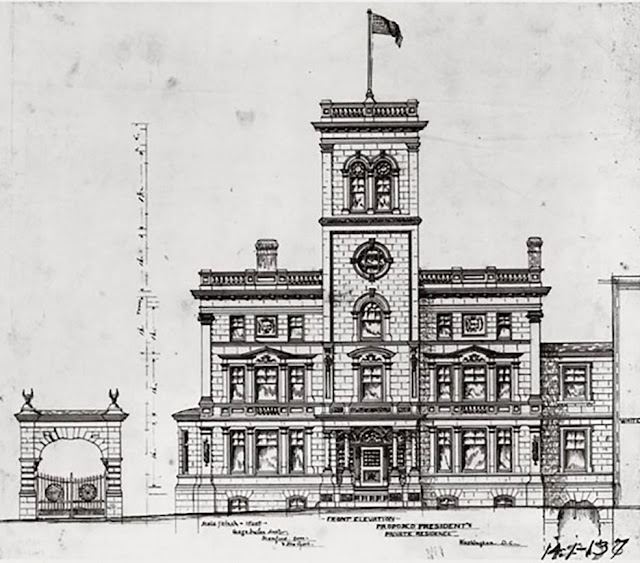

| George Inslee's proposal for a private residence in 1881 for President Chester Arthur |

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, several major proposals were made to alleviate crowding at the White House by erecting a new residence for the president and converting the old building to office and ceremonial use.

|

| Colored glass screen by Tiffany that was located in the Entrance Hall Peter Waddell, The Grand Illumination |

President Chester Arthur pressed for a new house in 1881, but had to settle for a refurbishment of the staterooms by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

|

| The lobby of the White House after renovations Hand-tinted photo, circa 1904 |

|

| The 19th-century conservatories were razed, and a new temporary executive office building, later called the West Wing, was erected |

|

| White House, Office Building, and tennis court, where the Roosevelt tennis cabinet met |

With a few exceptions, much of the complex we know today reflect the design of 1902 that preserved the White House as the home of the president.

|

| Colored glass screen by Tiffany that was located in the Entrance Hall |

One of the most legendary objects in The White House’s history was the colored glass screen by Tiffany that was located in the Entrance Hall. It was removed on the orders of new President Teddy Roosevelt in 1902, who supposedly wanted it smashed into little pieces.

Rumor has it that the tremendous lost screen was instead removed, auctioned off for $275, and eventually installed into the Belvedere Hotel in Maryland, which burnt to the ground in 1923. Some historians speculate President Roosevelt’s motivations in removing a national treasure might date back to his personal animosity to Tiffany, possibly inspired by the bitter litigation and dispute with the town of Oyster Bay during Tiffany’s acquisition of the property of "Laurelton Hall", originally public picnic grounds and an old hotel of the same name.

The Expansion that Never Was: 1889-1901

Truman Reconstruction : 1948-1952

Kennedy Renovation: 1961-1963