"La Ronda"

The plans reveal the mind of an architect who does not see the country house in strictly conventional terms. In such a way an ancient feudal castle might have been planned, though it would have had fewer baths. C. MATLACK PRICE 1936

|

| The home of Mr. and Mrs. Percival E. Foerderer at Bryn Mawr, built of stucco with a roof of Spanish tile. |

|

| The estate grounds, including a walled garden with a fountain adjacent to the dining room, were the work of landscape architect Louis A. Adams. |

|

| Garden fountain. |

PERHAPS it is true that the answer to our swift-moving mechanistic age is to be a romantic revival. Plenty of people believe that the natural reaction from any vividly motivated period is a period exactly opposite in feeling. It might seem like forcing this theory to rest its case on one house, particularly since it is a house designed by Addison Mizner. This man, we all know, who know anything about Florida, is definitely a romantic architect and it is probable enough that any house he might build, in any period or any clime, would be an expression of architectural romanticism.

So far as this mechanistic age is concerned, while the architects are performing prodigies with big buildings, incredible masses mounting skyward, they might as well admit to being baffled by the job of modernizing the individual house, particularly the country house. Human nature being what it is, people seem still to live more happily in a traditional environment than in an experimental one.

Even allowing that they find a certain kind of romance, which is largely thrill, in our great modern buildings, they mostly prefer another kind of romance, which is old human association, in their homes. Most of us could not break sharply with the past, even if we would; the continuity of human history is too potent, our love of places of known abode, of sequential civilization, is too much a part of us.

Certainly, Addison Mizner sees architecture as a link with a past that is more appealing, more interesting to him, than the most exciting present. He sees architecture as a link that may connect past with present civilization; old forms may be made to minister to the most modem and sophisticated technique of living. This, certainly, he has proved many times over at Palm Beach. No group of peoples could live in a more modernly contrived tempo, or in settings more completely transplant from the old world—in which there may be implications of some sort of baroque super-sophistication more the province of sociological than of architectural inquiry.

Click HERE to see the estate from 1948 onward. You can go through the decades and view the changes in the surroundings and the final demolition. BING view has "La Ronda" still extant, except for the east view, which shows its replacement.

|

| Above two photos are from 1938. |

In this house in Pennsylvania, the architect has carried northward that same romanticism which has inspired his work in Florida, here choosing to work in the Spanish Gothic manner of the old houses on the plains of Castile. It is a type of northern Spain, where the land is burned dry by the summer sun and bleakly swept by winter winds.

Spanish roof tile crowns walls of stucco, and the whole exterior has the random, informal massing of ancient villas and palaces. Recognize at the outset that there is this about the romantic in architecture—it wants the patine of time. All very to remember that the old villas, old palazzi, were once new—but we know them only as they have been softened and mellowed by centuries. Artifice may do much to achieve this, but the essence of it is the handiwork of time and the intangible spirit of an old place that comes from years of human life within its walls.

|

| The style of the Foerderer house is definitely Spanish Gothic, inspired by the beautiful houses on the plains of Castile. |

|

| Facing a three-sided walled courtyard, "La Ronda" is covered in smooth stucco with reconstructed stone trim and a roof of red barrel tile. |

|

| Original view, minus the gate, swept north down to an oval pond past lawn and tree. |

|

| These post top finials are made of cast stone. |

|

| Walled courtyard. |

|

| Courtyard fountain. |

|

| Breakfast room off courtyard. |

|

| View showing second floor servants wing. |

|

| View of the back of the house showing the group of Gothic Windows and the double flight of steps leading down to the tile-bordered pool. |

|

| Facing a three-sided walled courtyard, "La Ronda" is covered in smooth stucco with reconstructed stone trim and a roof of red barrel tile |

|

| West or library side. |

|

| View into library. Above was the sleeping porch off the master bedroom. |

|

| These salvaged cast stone gnomes were part of the frieze detailing above. |

There is a particular interest in this house, as in much of Mr. Mizner's work, in the use of various materials uniquely made under his direction. It is one of his means of getting particular results, of carrying the personal quality of of work beyond the limits of design and into actual execution. The trim of the exterior is made of reconstructed stone, softly rose-yellow in color and quite unlike any expected material. Within, much of the flooring is of Mizner tile, and the dining-room ceiling is copied, by a new process, from a room in Al Cal Henares, in Spain. Even the bronze sash and stained glass in the great hall came from the workshops organized by the architect: there is an interesting throw-back, here, to the days when architecture was more closely allied to building and to materials than it is today, to a time when the hand of the architect pervaded the whole structure.

Other effects are added from an appreciation of certain unique properties of materials from the workshops of Nature, as particularly in the floor and walls of the great hall, which are of coral stone brought up from the Florida Keys, stone peculiar in its ancient and intricate texture.

|

| The Great Hall in the Foerderer house with walls and floor of coral stone: heavy wrought-iron doors, Gothic arches about the windows and a vaulted cloister leading to a flying stairway. |

|

| Three double-height, pointed-arch windows overlook the sheltered patio and a cruciform-shaped pool on the lawn terrace. |

|

| Grand hall entry gates with period decoration done in the Spanish Revival style. |

|

| The coral was quite porous and pock marked with a warm soft brown tone that made for a nice contract against the cooler gray tonal, fancy limestone door and window surrounds employed at "La Ronda". |

|

| This hand crafted Gothic-style iron chandelier was the centerpiece to this great hall. |

|

| All woodwork, fixtures, and decorations at La Ronda, as well as most of its furnishings, were created at Mizner's Florida workshop. |

Downstairs the scheme is fairly obvious—an entrance vestibule, with lavatories right and left, then the Great Hall.

The great hall is entered through heavy wrought-iron doors, and above the entrance a vaulted cloister leads to a flying stairway that admits to the master's portion of the house. The hall is rib-vaulted and its decorations are largely ecclesiastical antiques of the period—old choir-stalls, 14th Century Bishop's chairs of wrought-iron, old copes—old things in a new-old environment, needing, mostly, the alchemy of age to blend them into a complete expression of old-world mediaevalism and association.

|

| Within, a small entrance vestibule leads to the two-story, rib-vaulted great hall finished in coral from Mizer's Florida Keys stone quarry. |

|

| The whole massive door opens, as does the smaller door within the door. |

|

| On either side of the entrance were faculties for guests. |

|

Hand made copper Moorish star from the entry hall.

|

|

| In this beautiful room, with its arched doorways and Gothic windows, the fittings and furnishings are all in harmony. The chairs are covered with old velvet and brocade, the sofas by the fireplace in brocatelle, and the rug is Hispano-Moresque from a convent near Toledo. The floor has a border of black, glazed Mizner tiles. |

|

| There are eight different windows each having a different musical motif. |

|

| There are also two matching stained glass doors. These doors originally slid open into the wall. The frames are bronze. |

|

| Arched window originally above sliding windows in the living room. |

|

| The huge stone fireplace in the living room is Gothic in feeling with antique andirons and a hand-wrought iron fire screen, The walls throughout this room are hung with antique tapestries, in keeping with the dignity of the fireplace and the moyen-age manner of the window structure. |

|

| Cast stone fireplace mantel with center keystone with profile of a knight in armor with shield and daggers that adorned the Living-room. |

|

| Designed and constructed specifically for "LaRonda". Giant firebox opening 7' x 7'. |

"Painstakingly" removed piece by piece and meticulously labeled for re-assembly.

|

|

| Opening into Loggia. |

|

| Beneath a richly coffered ceiling, copied from a Spanish original in the Alcala Henares, a single-plank dining room table expanded to seat 24 people. Wall coverings in the dining room were based on a pattern found in Italy's Davanzati Palace. |

|

|

| Decorative cast stone entryway Opening measures 96" high x 60" wide. |

The romantic keynote of the whole house finds a strong expression in the dining room, with its deeply coffered ceiling and walls frescoed in a pattern from the Davanzati palace in Italy. The 17th Century table is made from one solid plank eighteen feet long, and chairs are upholstered in a soft crimson velvet.

In addition to the large table a smaller antique table for family use has been placed in the dining room, for use when there are no guests, or for small, informal luncheons. When it is necessary to have a very long table, this five foot table is joined to the larger one, giving a length of twenty-three feet.

|

| The Library. |

|

| Library bar. |

|

| Zinc coated copper sink outlined in solid Oak from the wet bar. |

|

| Set in an alcove at the great hall's east end, the main stairs lead to a second-floor balcony. |

|

| Three additional bedrooms are located in the east wing, along with a nursery and servants' quarters. |

|

| Spanish Gothic style chandelier with hand hammered iron and ornate cast brass.. Originally adorned the second floor hall. |

|

| Wrought iron railing sections were salvaged from the second floor cloister. |

|

| Two bedrooms and the master suite are accessed from the west end via an encaged hanging stair. |

|

| Mizner made sure every detail was top notch so he personally oversaw the ironwork at his own company. |

|

| The salvaged iron door that closed off the master suite. |

|

| A separate circular stair tower leads to the third floor observation room in the larger of the two towers; the smaller tower houses a children's playroom and sleeping porch. |

|

| Hand hammered iron three story staircase. |

|

| Detail - hand hammered iron three story staircase. |

|

| Hand hammered iron three story staircase. |

|

| Detail - hand hammered iron three story staircase. |

|

| Cast stone fireplace mantel from the "mirador" |

|

| Moorish round skylight originally adorned the second floor West wing. |

At this point a fantastic idea assails the writer. The year is 1330, or perhaps 1430—not 1930. This half of the house could be defended against the other half, or against marauders, who may have forced their way into the Great Hall. Imagination sees a "costume piece" after the best manner of Sabatini, in a setting peculiarly designed for it. One good swordsman would hold the flying stairway against a score; another would hold the circular stair, unless its lower door had been locked in time; servitors and men at arms, perhaps, pouring from the servants' wing, would be engaging the enemy in a battle on the stair that leads up to the cloister. Steel upon steel—the Siege of "La Ronda"—sheer fantasy, which the writer must blame upon the architect for creating such a perfect setting for that kind of a costume piece, with a plan as admirably designed for defense before the general use of artillery! Such affairs built history in the ancient houses and castles of Europe, whether or not that history was always entirely to the liking of the master and the chatelaine at the time it was being enacted. By association some of the glamour of those more romantic days will come with time to rest even upon this very new castle in Pennsylvania.

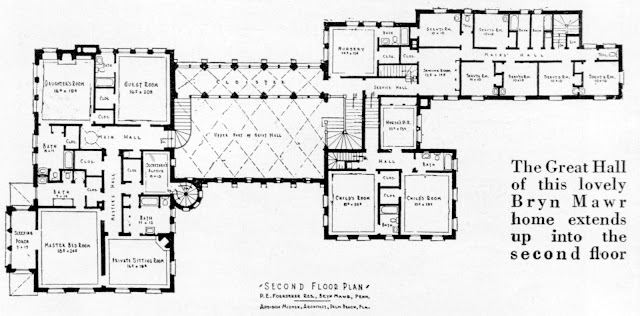

It is 1930, so we must return again to the plans, and ascend that stairway at the end of the Great Hall—that stairway where, a moment ago, imagination saw a brave show of sword-play in the defense of the cloister. . . . To the right, through a doorway, stairs lead up to another unit of the castle plan (again designed as though for the defense that would have been ever in the mind of the medieval builder). Here are two rooms and bath for two children, a room and bath for their nurse, and a stair upward from a hall to the childrens sleeping porch—an airy tower—and an alcove for the nurse.

It was thus, in effect, that ancient castles were planned, or grew, and in the architectural manner of "La Ronda" it all seems strangely logical and appropriate enough here.

The facts about a house, its plans and its furnishings are interesting but not so interesting as the total effect that has been achieved. The criticism leveled against the house that derives directly from an historic period has been that it contributes nothing to any expression of the life of our own time. The acceptance of the premise underlying this criticism, however, does not lead to any satisfactory conclusion. There is a confusion of background and foreground. The fact seems to be that most of us seem to live more happily against a background of past civilization than in a foreground of sociological and aesthetic experiments.

And no matter how definitely an architect's choice of historic style may derive from a period, there is still plenty of room for him to endow his work with a very personal touch. It is in this that Addison Mizner has always been particularity successful. Imbued with a strong feeling for romanticism architecture, he had devoted much effort to the making of materials which would most effectively realize the spirit of his work. He is not a user of unimaginative formula in design. In this house, he has created forms that invite time to add its master touch to the completion of a beautiful picture, a house that grows only more lovely with age, more charming as vines cover its walls. C. MATLACK PRICE 1936

|

| Original garage and servant quarters. |

|

| Back side of garage. |

|

| Original Gatehouse |

|

| PERCIVAL E. FOERDERER(1884-1969)Foerderer was the third generation in the family leather business and his father invented a special chrome process for treating goatskins to create soft, pliable leather(Patent leather).Known as "Mr. Jefferson" because of his long time involvement with the development of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. In 1925 he purchased the 250-acre Bryn Mawr estate of former U S. Attorney' General Wayne McVeigh. Mizner demolished the 1882 McVeigh residence by Theophilus P. Chandler. Jr. and completed the 51-room "La Ronda" in 1928. |

|

| Addison Mizner |

Unbelievably "La Ronda" was considered dark and dank by some. Despite efforts by a number of groups the last Mizner designed home was demolished in early October 2009.

Click HERE to read a variety of news articles relating to the demise of the property. HERE to view a community action website that chronicled the efforts to save "La Ronda". Many additional links for photos, videos of the interior and comments that highlighted the tragedy. Two links - HERE and HERE - are local TV broadcasts, one involves a plan to move the house to an adjacent lot, the other a story titled COUNTDOWN TO DEMOLITION.

A BEHIND THE WALLS article tells the story of Florence, the hidden daughter of the Foerderer's. Mignon was the oldest, Florence the middle child and Shirley the youngest. An interesting Upstairs, Downstairs story can be found HERE. "And everyone who lived or worked there remembers Christmas at La Ronda. Cooking smells wafted down the corridors from a cast-iron stove as big as a buffalo. A hundred radiators clanked with the startup strain of heating the Bryn Mawr mansion’s many rooms."

The Foerderer Family Papers are kept at The Historical Society of Pennsylvanian. The family had a townhouse in Philadelphia and were known to summer in Seal harbor, Maine. Percival grew up at Glen Foerd.

***Most of the color photos posted here were done by Carla Zambelli.***

|

| On the first day of October 2009 the buyer was allowed to bring in equipment to bulldoze what remained of the house... |

|

| .....and by the afternoon of the first day a fair portion of the building was little more than a pile of rubble. |

|

| THE END. |

|

| What was. |

|

| What is - nice enough - hardly a worthy replacement. |

Wooden with built in mirror and lower bracketed shelf. Hand painted frescoes adorn both interior and exterior doors done in the Mediterranean Revival Style.

Where in the house this was placed I can't say??? |

|

| Comprised of nearly 50 hand blown glass rondels on a drop of turquoise blue. I don't know specifically where this was located in the house??? |

|

| Custom hand hammered iron lantern. Where it hung is unknown to me??? |

|

| BOOKPLATE - EX-LIBRIS - FROM THE LIBRARY OF PERCIVAL & ETHEL FOERDERER |

It's quite the sad (if not appalling) tale of a work of art so publicly destroyed. At least most of the what could be salvaged was and will continue on.

ReplyDeleteClearly what was built is nothing on peer with its predecessor. In fact there are a slew of homes on the Main Line - for sale - that look just like the new one built. Its truly baffling as to why the owners (Joseph and Sharon Kestenbaum) insisted upon their course of action.

Oh yes that's right - they claimed La Ronda lacked air conditioning as one of the reasons for it to be entirely replaced. Amazing.

What is equally disturbing is that there were honest offers to purchase the house and move it onto an adjacent property yet the owners refused to cooperate with the town, preservationists and pushed forward with demolition. A sad loss for future generations and sadly reflective of dim witted owners displaying extreme ignorance of history and a lack of understanding of what makes this world unique. Their big and dull grey stone house is a turd in comparison to La Ronda. RT

ReplyDeleteIn their haste to destroy this beauty, it is disappointing to see so many ornamental and architectural items, carvings, scuppers, mouldings, roof tiles, even those amazingly beautiful gothic-style windows ground into a heap of dust and debris. Outrageous that such misguided owners could be so selfish and arrogant not to see the bigger picture beyond their own deluded self-importance. NYarch

ReplyDeleteWhat destroyed these mansions is what causes them to be built: avarice...

ReplyDeleteextreme greed for wealth or material gain.

My name is Robin Clem, my parents bought La Ronda in the late 70’s sold in 1981 and moved back to Texas. I can remember my parents redid the entire inside of the home including plumbing, electrical, and put a whole new kitchen in leaving the original 12 burner stove. We lived in the carriage house while the renovations went on. I can remember playing on the grounds in the snow and people would drive by just to see the place. It was exquisite in every way imaginable. There was a man made pond on the property that I dreamed of ice skating on but for some reason never did. My mother cleaned the gardens and used a John deer tractor to mow the 14 acres. My parents worked so hard to bring La Ronda back to life. My dad’s job transferred him in 1982 and we ended up moving to Texas. This was a once in a life time experience for me to say the least.

ReplyDeleteI think I met your sister during the demolition a couple of days. It was terrible when they opened the great hall to the sky use.

ReplyDeleteI took about 1 photo every 5 minutes so that if you flipped them you could watch the whole demolition. It was a terrible and memorable day…