"WHY did you build it on one floor?" "Is it adapted from Jefferson's "Monticello"?" "Was it suggested by the Petit Trianon?" "Was it inspired by a Greek temple?" "Did those Palladian houses on the Brenta Canal influence you?" "Why did you build it on one floor?" Those are the repeated questions we have to answer.

It is pleasant to have a house that suggests so many origins, but it really was inspired by none of them—American, French, Greek, or Italian. Its real inspiration was the gate-house of Kimbolton Castle, built by Robert Adam. True, the gate-house was not of white painted brick, but of grey stone. It was a long, low structure with no wings but from its lovely facade, I began. I love houses built around large courtyards, and I love high ceilings, and there you have the reason for a one-storey house. You can have neither large courts nor high ceilings in small houses of more than one story. To get the same low, gracious effect, you will have to build a house four times as large.

|

| "LITTLE IPSWICH" by RUBY ROSS WOOD |

When I had drawn my ideal plan, after months of changes I took it to Mr. Delano, and be made a house of it. He stood it on its end and gave it form and substance and sense and dignity, and, we confess, we think great beauty, as well. He placed it on the west side of our pond, to that it might look across a vista between two great oaks whose trunks were just fifty-two feet apart, and so we made our courtyard fifty-two square. The afternoon sun is consequently on the front of the house, and the paved court is in the shadow in the afternoon. I say the paved court, because there is a greater white-walled court one hundred feet square in the front of the house.

You enter a round hall with a domed ceiling, painted from Isabella d'Este's lovely ceiling with the hearts, in the palazzo del Te, in Mantua. We went all the way to Italy to see that ceiling, and it was worth it. The original ceiling was in many colors with brown-red hearts, but ours is painted in tones of terra-cotta and white and black-brown, because the hall floor is of cream and black-brown terrazzo. The only furnishings are four English terra-cotta figures of the seasons, signed "Coade, Lambeth, 1791."

Before you enter the house, you are aware of our hobbies—horses, swans, and sphinxes. Two small stone sphinxes from Italy sit on the wall of the entrance court and another pair is on the high retaining wall on the south side of the court. On the dome, a gilded swan is the weather-vane. The house is full of swans and sphinxes and horses and there are real horses in the stables and real swans in the pond, but, so far, we haven't found a real sphinx.

|

| THE ROUND HALL IN MR. AND MRS. CHALMERS WOODS HOUSE |

As you enter the round hall, you look straight across the pond through the two great oaks to the riding-field beyond.

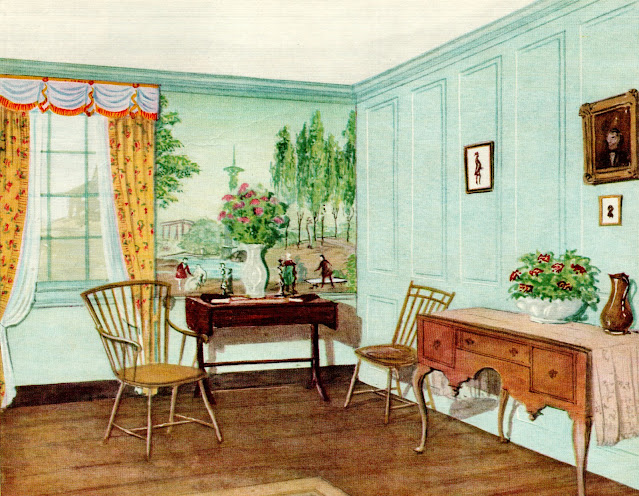

On the left as you enter is the dining-room. In front of you is the loggia projecting into the paved court. On the right is the library, through which you must pass to reach the long hall of the south wing.

The library began from an Adam overmantel that Isabella Barclay found in an old London house, a mysterious affair, because some of its detail is undoubtedly English, and other detail is French. It is a circle of mirror upheld by two sphinxes and garlanded with two wreaths of flowers, a la Grinling Gibbons, standing free from the mirror. An urn surmounts the mirror. The other great treasure of the room is a Directoire Aubusson rug, with four great swans. I really suffered in having to put it on the floor of this room, which is necessarily a passage by day, but there it belongs. Over the windows, classic paintings of white figures on black are inset. The books go all the way to the ceiling, on all four walls. The room is built of pine stained to match the tone of the lime-wood of the Adam overmantel as nearly as possible.

From the library, you enter a long corridor with French windows opening onto the paved court on the north ride, and on the south side are the doors that lead into my bedroom and my husband's bedroom. A small writing-room and bath open from bedroom, and a bath lies between my room and my husbands. At the extreme end of this corridor, you enter the living-room, which has a French window the north opening into the court, another to the south opening into a sunken flower-garden, and a great flower-filled bay-window that looks out over the pond. There is another door that opens onto a long south terrace, outside our bedrooms. From this terrace, you go up a flight of steps to the swimming pool, which is completely enclosed by a high hedge of spruce with tall cedars back of it

Going back to the entrance-hall, you enter the dining-room. You are faced by the mantel wall, which has two doors, one leading to a guest-room and bath, and the second to the pantry. This wall has a long, curved alcove in which the mantel is set. Again, there is a long corridor, leading to the servants hall, kitchen, and servants bedrooms. At the extreme end of this wing, there are two guest-rooms and a bath, which occupy the relative space as the living-room in the south wing. So you have the geography of the house.

The dining-room is painted a very pale grey, and has curtains of superb Directoire satin in very dark blue patterned with enormous white swans and conventional Directoire wreaths and borders. I have tried to keep this room as cold as possible, with mahogany furniture, black leather chairs, a set of black-and-white engravings by Canova, gilt mirrors, and an old black lacquer high-boy. Four ivory figures of the seasons are on the grey-and-white marble mantel, and a great white Greek vase, with projecting figures of horses is on the top of the high-boy. The room gives the impression of black and white, in spite of its mahogany and dark blue curtains.

|

| MRS. WOOD'S BEDROOM IS BOTH FRENCH AND ENGLISH |

In this short space, I can only mention briefly the things that brought the various rooms into being. My own room has the most beautiful old French floor, the squares made up of stars and compasses in black and white wood inlaid in oak. Kathleen Tysen found this floor for me in France, as she knew my old collection of stars. I was fortunate in finding a very small four-poster Adam bed painted in very dark green and a painted wardrobe of the same period. This Adam furniture quite at home with the dark brown marble mantel and carved wood overmantel, which are French. The room is a mixture of French and English furniture of about the same period.

My husband's room has one of our greatest treasures on the mantel wall, an old hunting-frieze discovered in a house in Roanoke. Virginia, which is supposed to be the earliest known American painting of this sort. The curtains in his room are of old flowered serge. The rug is embroidered Persian felt made from the lining of a tent, which, strangely enough is the most durable rug in the house. There are a Chippendale mahogany secretary, a walnut cheat of drawers, two leather chairs and a painted bed, which does not seem to mind its masculine surroundings.

|

| OLD LEATHER SPORTING PANELS FROM ENGLAND |

In the living-room are our leather panels of which we are very proud. They came from Longnor Hall, in Shropshire, and are dated 1723. There are three of them, depicting racing, one wrestling, and the third stags hunting. They are of the most luminous quality, the leather having been first covered with silver, then gold, and then painted. We hope they are by Thomas Wooten, but we can not prove it. The living-room has a very large rug, which is also debatable, because while it looks English, its border is undoubtedly Persian. It has an olive-green ground with garlands of pink flowers and circles of enormous white acanthus-leaves. The ground of this rug it olive-green, and from this I painted the walls of the room. The curtains are of a little darker olive-green damask. There is a fine Japanese screen, very early, on each panel of which there is a horse in a stall. I found a pair of these screens in London, and, not having a place to use two, had them mounted back to back as one screen. so that both sides can be enjoyed.

The long corridor leading from the library to the living-room is papered with a Chinese paper of the Queen Anne period. The corridor was so narrow that there was no room for furniture, and to hang pictures would mean too many, so I used this old paper, which fills the hall with decoration. The curtains are of taffeta made up of checks in every color of the rainbow, which looked very modernistic when I found it in London, but, as all of the colors are repeated in the wall-paper, seems quite conventional in this hall.

|

| PRIMROSE PATH |

From the south terrace, there is a long green garden, which opens a cedar vista. You look down the green garden to an enormous oak-tree in the woods, a most extraordinary Italian effect. The green garden is made up entirely of grass and ivy, like a French garden. As we live here all the year round, we have tried to use material that will be green in winter, as well as in summer.

|

| VIEW FROM REAR COURT ACROSS POND |

|

| REAR, POND SIDE |

Together we have planned this house

With love have sought, brick and stone

To model here a perfect home

So fashioned that the shadows fall

In pleasant patterns wall,

And so disposed that rooms have sun,

With space and air i every one.

It's finished . . . Only time can

Whether we've done it ill or

For me, who love both you and it

The time has come to write "exit."

Before I leave one thing I do:

Pray God that peace may be you.

North Shore Long Island: Country Houses, 1890-1950 by Paul J. Mateyunas

Completed in 1928, for Chalmers Wood Jr. (1883-1952) and his second wife, the interior designer Ruby Ross Wood (1881-1950). The Woods named the house for Chalmers' childhood home in Massachusetts where his mother's family (the Appletons) had lived since 1637.

Chalmers survived his wife by two years. After his death in 1952, the house became the summer home of Count Giorgio Uzielli (1903-1984), a New York stockbroker from a notable Florentine banking family related by marriage to the Rothschilds. He renamed it "The Lakehouse" though locally it was still referred to as Little Ipswich. After the Count died in 1984 the house stood empty, gradually falling into disrepair and becoming victim to vandalism. In 1995, Little Ipswich was demolished and its 28-acres were sold for development. Today, 21 houses known as the Pironi Estates stand on the grounds.

Architect Delano liked the house so much he chose it as the backdrop for his official portrait. https://americanaristocracy.com/houses/little-ipswich

Follow THIS LINK for all past posts on "Little Ipswich".